Introduction

This enquiry proceeds from the idea that the camera is not a passive and faithful recorder of the visual, but has the ability to transform its subject, giving to it unexpected qualities, producing novel viewpoints, altering the perceived size and scale of the thing reproduced. This has led to consideration of the camera as an active presence within the filming situation, a tool that can be wielded by the artist to transform sculptural objects, but also as one which structures a type of artistic activity happening both in front of the camera and in anticipation of the event of filming.

The focus of the research is two-fold. Firstly, it looks towards the camera’s ability to transform perceived qualities and put the status of objects into question. Secondly, it looks towards the sculpture and what its particular physical, aesthetic, symbolic and associative attributes afford or suggest in the filming situation. The art practice constituting the core of this research therefore falls into two parts: that of filming sculpture and of making sculptures to be filmed. Both of these activities are in some sense perverse. Why film sculptures? Why not exhibit the things themselves? And similarly, why make sculptures to be filmed? Why not make them to be physically encountered? This is the beginning of an ontological questioning that runs throughout the research. Does the intention to film and not exhibit the objects invalidate their status as sculpture? Should they be more appropriately considered as props or models or pieces of set? Although there is some knowledge to gain from this type of questioning, what is really at stake is what filming can enable. The questions would then be: what can be revealed that might otherwise go unnoticed? And how does creating sculptures to be filmed effect the process of making? What happens that otherwise would not?

The process of filming is seen as a productive dynamic between sculpture, camera (filming situation) and artist; the camera and the process of filming constituting an integral part of the making process through which the form and meaning of the sculpture is discovered and articulated. ... Acknowledging that a research project of this scale could not interrogate every aspect of this dynamic the practical research has explored a number of possibilities including the following: the creation of reified and enigmatic images, the conflation of two and three dimensions, anthropomorphic or theatrical appearances, the ways in which certain formal qualities and surface textures respond to lighting and camera angle, and sculptures which suggest movements and, extending from this, collections of sculptural objects which can be ‘played with’. This has been accompanied by the use of a number of different analogue and digital film and video formats – 16mm, VHS, SD, HD, Slow motion - and the creation of sculptures in a number of traditional materials – wood, plaster and ceramic.

Two types of sculpture-camera relationship have emerged as central to the research practice. The first is one in which the sculpture is explored by the camera as a mode of visual experience. How the ‘look’ of the sculpture might be transformed in scale, or texture or colour through different modes of filming – oblique camera angles, close-up and distance shots, slow motion, lighting effects and tracking shots. This might also be phrased as an exploration of the ways in which certain types of filming express the reality of the sculptures and which aspects they emphasise or transform – how for example, when lit from the side, the industry standard high definition camera expresses the texture of chiselled plaster objects offering a heightened awareness of the tactility of the sculptures’ surfaces and making this the focus of the viewer’s attention.

The second significant sculpture-camera relationship developed directly from the work in the film studio and concerns the practicalities of handling different kinds of camera equipment and the ways in which these affordances or constraints enable and inflect creative practice. For example, when shooting 16mm film, a clockwork Bolex camera must be wound-up and only shoots in thirty second bursts, the focus being set manually using a tape measure, producing a particular rhythm and working speed. Conversely a hand-held VHS camera begins recording with the touch of a button and will run for an hour allowing for extended periods of uninterrupted improvisation and exploration. Kingston School of Art’s Phantom slow motion camera is cumbersome, must always sit upon a fixed tripod and requires so much light that it must always be set with a fully open aperture meaning that only a very short depth of field is available. Equally video formats record in different ways, some onto tape enabling in-camera editing, whilst others produce individual video files which must be strung together, or perhaps suggest different ways of sequencing when in the editing suite. Some cameras respond well to highly contrasted lighting, others produce a flattened low contrast image, meaning that certain formal and material qualities are rendered in vastly different ways.

Similarly the practical work in the film studio has looked to the affordances and qualities of the sculptures themselves, employing a range of forms and materials intended to prompt various types of exploration. From this stems a further understanding of the camera/sculpture relationship linked with performance, in which the camera is understood to delineate a temporal and spatial arena in which action can take place. Action which is inflected by the camera’s presence and is responsive to the particularities of the situation and the qualities of the objects, which shift attention away from the technicalities of visual reproduction towards a very human negotiation with physical objects and equipment.

It was an early assumption during this research that my experience of working practically in the film studio would allow me to make better, more sophisticated or strategic decisions when constructing sculptures to be filmed. That the sculptures would in a sense ‘improve’ as my own knowledge and skill developed. In the event what this produced were filming situations in which the outcomes were already envisioned and to a large extent pre-determined. What could be seen as the success of the sculptures did not lead to genuine discovery but rather showcased existing knowledge. This was particularly evident in the film Pieces of Wood (2016) for which I constructed small wooden sculptures which could be thrown through the air in spinning trajectories and filmed by the Phantom slow motion camera creating images in which the sculptures appeared to float and slowly revolve. Subsequently it was felt necessary to create sculptures with less narrowly defined and pre-determined qualities in order that the process of filming could maintain an unexpected, non-strategic and symbiotic character leading to genuine surprise and discovery.

In this sense I have used my developing knowledge and experience of working with particular camera and film/video formats and the ways in which they interact with certain materials and formal qualities in order not to predetermine how a given sculpture will interact with the camera, nor to create objects which I am confident will do a particular job when filmed – as if the sculptures were an excuse to explore the technical possibilities of the media – but to create sculptures which act as open-ended propositions or prompts for action in order to discover the possibilities of the sculptures through filming.

THE CONTEXT

A number of key artworks, modern and contemporary, have been pivotal in articulating these ideas and form a field of exploratory practice to which this enquiry contributes. These include the 16mm film Made in ‘Eaven (2004) by Mark Leckey which pictures a highly polished Jeff Koon's bunny that reflects the room around it curiously absent of the camera that would seem to record the image; Laure Prouvost’s Wantee (2013) in which the artist creates a film set - supposedly the home of her Grandparents - in which sculptures referencing the work of Kurt Schwitters are reframed as household objects within a bizarre yet compelling fictional narrative; and Lazlo Moholy-Nagy’s use of the camera in the film A Lightplay: Black White Grey (c.1926) to explore the sculptural construction that became Light Space Modulator (1930) creating shifting patterns of light and shape. All these artists, it is proposed, have used the camera and the moving image as a means to explore and transform sculptural form, to give sculptural qualities to everyday objects, and to extend or put into question the reality of the things pictured.

As the practice of filming sculpture is not usually articulated as a distinct movement or genre within art history, my research necessarily intersects with a number of distinct historical periods and art practices including artists’ film and photography, expanded forms of sculpture and performance art. The research gathers these diverse practices within its frame of reference whilst acknowledging that the artists cited did not dedicate themselves purely to the practice of filming/photographing sculpture. What links them all is that they have used the camera to explore and extend sculptural form rather than seek to straight-forwardly document pre-existing works.

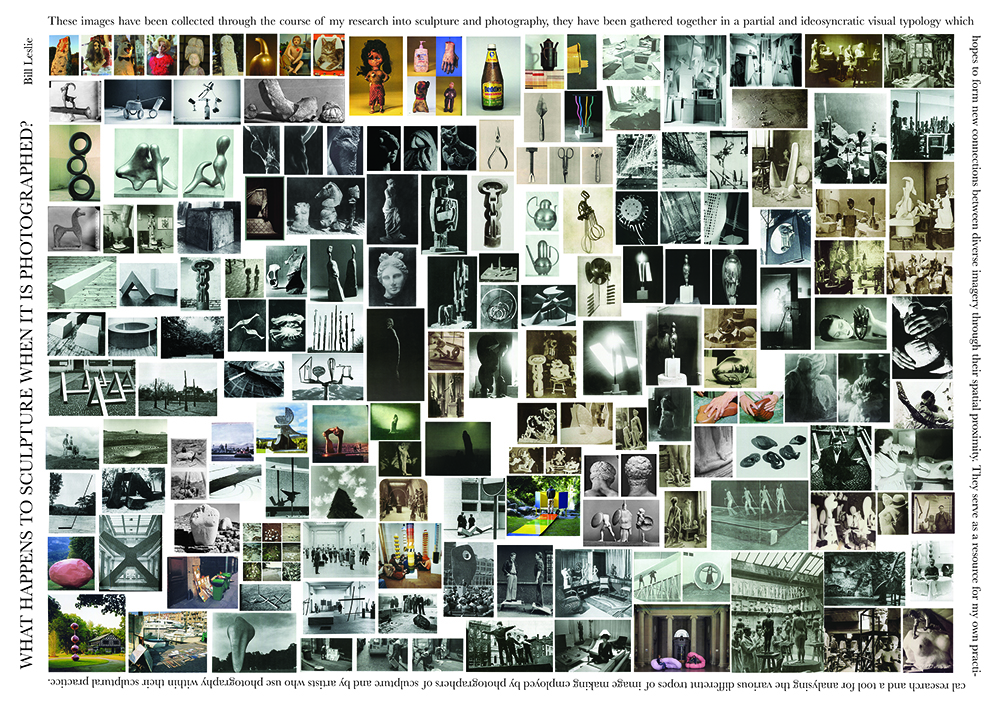

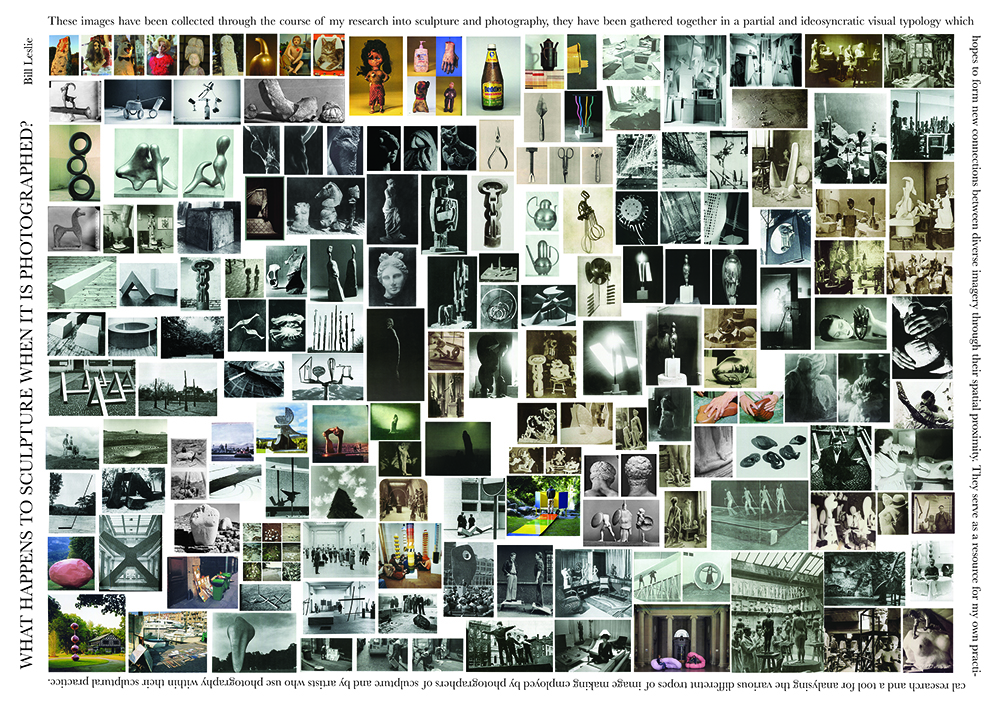

Equally important to the early development of the research was the creation of typology poster which brought together images taken from the many books and articles on sculpture and photography which were initially consulted. This poster allowed for an initial consideration of the ways in which sculpture has been pictured since the early days of photography and the priorities and agendas these forms articulate. This poster was a useful means of visually grouping the images I had discovered and formed a palette of forms with which to begin creating my own objects.

Two films by John Smith, The Black Tower (1985-7) and Dad’s Stick (2012) have been informative. Whilst not addressing sculpture directly, they explore the reality of pre-existing objects within fictional and autobiographical frames. Equally his film Blight (1994-6) in which objects on a demolition site appear to move autonomously, the presence of human endeavour concealed but lingering around the edges of the frame, has had significant impact on the research.

Eva Rothschild’s film Boys and Sculpture (2012) is also an important point of reference, showing a room full of modernist-style sculptures into which enter a group of young boys who progressively dismantle, destroy and reuse the elements of the sculptures for their own devices. The camera allows for a capturing of this sculptural manipulation in progress, at a point of exhibition which would, under standard gallery conditions, have been considered finished and closed to further physical engagement. This is not simply an effect created by the situation, but also by the sculptures themselves. Whilst they initially appear to be made of solid, hard materials, when touched they yield and bend and easily fall apart, in a way that might be seen to encourage the boys’ tactile curiosity. This intersects with developments in this research in which the camera is discovered not only to be a tool for visually exploring sculptures but as enabling a space in which action can take place: a presence that can be performed to, or in front of. This has enabled a certain type of sculptural object to be made, which prompts or affords different interactions, movement or handling, through its formal, material and kinetic qualities. More profoundly the camera produces a space in which a new type of sculpture comes into being. One which is not tied to a particular gallery context, nor delineated by conventional art gallery etiquette, imbuing it with the aura of the ‘art object’. Rather the joint practices of creating, filming and presenting sculptures made to be filmed offer spaces in which to rethink our relationships to sculptural objects, to think about what sculpture might be and to produce artworks which are neither tied to a gallery context, nor finished and fixed but which are mutable invitations to further practical investigation and thought.

The focus of the research is two-fold. Firstly, it looks towards the camera’s ability to transform perceived qualities and put the status of objects into question. Secondly, it looks towards the sculpture and what its particular physical, aesthetic, symbolic and associative attributes afford or suggest in the filming situation. The art practice constituting the core of this research therefore falls into two parts: that of filming sculpture and of making sculptures to be filmed. Both of these activities are in some sense perverse. Why film sculptures? Why not exhibit the things themselves? And similarly, why make sculptures to be filmed? Why not make them to be physically encountered? This is the beginning of an ontological questioning that runs throughout the research. Does the intention to film and not exhibit the objects invalidate their status as sculpture? Should they be more appropriately considered as props or models or pieces of set? Although there is some knowledge to gain from this type of questioning, what is really at stake is what filming can enable. The questions would then be: what can be revealed that might otherwise go unnoticed? And how does creating sculptures to be filmed effect the process of making? What happens that otherwise would not?

The process of filming is seen as a productive dynamic between sculpture, camera (filming situation) and artist; the camera and the process of filming constituting an integral part of the making process through which the form and meaning of the sculpture is discovered and articulated. ... Acknowledging that a research project of this scale could not interrogate every aspect of this dynamic the practical research has explored a number of possibilities including the following: the creation of reified and enigmatic images, the conflation of two and three dimensions, anthropomorphic or theatrical appearances, the ways in which certain formal qualities and surface textures respond to lighting and camera angle, and sculptures which suggest movements and, extending from this, collections of sculptural objects which can be ‘played with’. This has been accompanied by the use of a number of different analogue and digital film and video formats – 16mm, VHS, SD, HD, Slow motion - and the creation of sculptures in a number of traditional materials – wood, plaster and ceramic.

Two types of sculpture-camera relationship have emerged as central to the research practice. The first is one in which the sculpture is explored by the camera as a mode of visual experience. How the ‘look’ of the sculpture might be transformed in scale, or texture or colour through different modes of filming – oblique camera angles, close-up and distance shots, slow motion, lighting effects and tracking shots. This might also be phrased as an exploration of the ways in which certain types of filming express the reality of the sculptures and which aspects they emphasise or transform – how for example, when lit from the side, the industry standard high definition camera expresses the texture of chiselled plaster objects offering a heightened awareness of the tactility of the sculptures’ surfaces and making this the focus of the viewer’s attention.

The second significant sculpture-camera relationship developed directly from the work in the film studio and concerns the practicalities of handling different kinds of camera equipment and the ways in which these affordances or constraints enable and inflect creative practice. For example, when shooting 16mm film, a clockwork Bolex camera must be wound-up and only shoots in thirty second bursts, the focus being set manually using a tape measure, producing a particular rhythm and working speed. Conversely a hand-held VHS camera begins recording with the touch of a button and will run for an hour allowing for extended periods of uninterrupted improvisation and exploration. Kingston School of Art’s Phantom slow motion camera is cumbersome, must always sit upon a fixed tripod and requires so much light that it must always be set with a fully open aperture meaning that only a very short depth of field is available. Equally video formats record in different ways, some onto tape enabling in-camera editing, whilst others produce individual video files which must be strung together, or perhaps suggest different ways of sequencing when in the editing suite. Some cameras respond well to highly contrasted lighting, others produce a flattened low contrast image, meaning that certain formal and material qualities are rendered in vastly different ways.

Similarly the practical work in the film studio has looked to the affordances and qualities of the sculptures themselves, employing a range of forms and materials intended to prompt various types of exploration. From this stems a further understanding of the camera/sculpture relationship linked with performance, in which the camera is understood to delineate a temporal and spatial arena in which action can take place. Action which is inflected by the camera’s presence and is responsive to the particularities of the situation and the qualities of the objects, which shift attention away from the technicalities of visual reproduction towards a very human negotiation with physical objects and equipment.

It was an early assumption during this research that my experience of working practically in the film studio would allow me to make better, more sophisticated or strategic decisions when constructing sculptures to be filmed. That the sculptures would in a sense ‘improve’ as my own knowledge and skill developed. In the event what this produced were filming situations in which the outcomes were already envisioned and to a large extent pre-determined. What could be seen as the success of the sculptures did not lead to genuine discovery but rather showcased existing knowledge. This was particularly evident in the film Pieces of Wood (2016) for which I constructed small wooden sculptures which could be thrown through the air in spinning trajectories and filmed by the Phantom slow motion camera creating images in which the sculptures appeared to float and slowly revolve. Subsequently it was felt necessary to create sculptures with less narrowly defined and pre-determined qualities in order that the process of filming could maintain an unexpected, non-strategic and symbiotic character leading to genuine surprise and discovery.

In this sense I have used my developing knowledge and experience of working with particular camera and film/video formats and the ways in which they interact with certain materials and formal qualities in order not to predetermine how a given sculpture will interact with the camera, nor to create objects which I am confident will do a particular job when filmed – as if the sculptures were an excuse to explore the technical possibilities of the media – but to create sculptures which act as open-ended propositions or prompts for action in order to discover the possibilities of the sculptures through filming.

THE CONTEXT

A number of key artworks, modern and contemporary, have been pivotal in articulating these ideas and form a field of exploratory practice to which this enquiry contributes. These include the 16mm film Made in ‘Eaven (2004) by Mark Leckey which pictures a highly polished Jeff Koon's bunny that reflects the room around it curiously absent of the camera that would seem to record the image; Laure Prouvost’s Wantee (2013) in which the artist creates a film set - supposedly the home of her Grandparents - in which sculptures referencing the work of Kurt Schwitters are reframed as household objects within a bizarre yet compelling fictional narrative; and Lazlo Moholy-Nagy’s use of the camera in the film A Lightplay: Black White Grey (c.1926) to explore the sculptural construction that became Light Space Modulator (1930) creating shifting patterns of light and shape. All these artists, it is proposed, have used the camera and the moving image as a means to explore and transform sculptural form, to give sculptural qualities to everyday objects, and to extend or put into question the reality of the things pictured.

As the practice of filming sculpture is not usually articulated as a distinct movement or genre within art history, my research necessarily intersects with a number of distinct historical periods and art practices including artists’ film and photography, expanded forms of sculpture and performance art. The research gathers these diverse practices within its frame of reference whilst acknowledging that the artists cited did not dedicate themselves purely to the practice of filming/photographing sculpture. What links them all is that they have used the camera to explore and extend sculptural form rather than seek to straight-forwardly document pre-existing works.

Equally important to the early development of the research was the creation of typology poster which brought together images taken from the many books and articles on sculpture and photography which were initially consulted. This poster allowed for an initial consideration of the ways in which sculpture has been pictured since the early days of photography and the priorities and agendas these forms articulate. This poster was a useful means of visually grouping the images I had discovered and formed a palette of forms with which to begin creating my own objects.

Two films by John Smith, The Black Tower (1985-7) and Dad’s Stick (2012) have been informative. Whilst not addressing sculpture directly, they explore the reality of pre-existing objects within fictional and autobiographical frames. Equally his film Blight (1994-6) in which objects on a demolition site appear to move autonomously, the presence of human endeavour concealed but lingering around the edges of the frame, has had significant impact on the research.

Eva Rothschild’s film Boys and Sculpture (2012) is also an important point of reference, showing a room full of modernist-style sculptures into which enter a group of young boys who progressively dismantle, destroy and reuse the elements of the sculptures for their own devices. The camera allows for a capturing of this sculptural manipulation in progress, at a point of exhibition which would, under standard gallery conditions, have been considered finished and closed to further physical engagement. This is not simply an effect created by the situation, but also by the sculptures themselves. Whilst they initially appear to be made of solid, hard materials, when touched they yield and bend and easily fall apart, in a way that might be seen to encourage the boys’ tactile curiosity. This intersects with developments in this research in which the camera is discovered not only to be a tool for visually exploring sculptures but as enabling a space in which action can take place: a presence that can be performed to, or in front of. This has enabled a certain type of sculptural object to be made, which prompts or affords different interactions, movement or handling, through its formal, material and kinetic qualities. More profoundly the camera produces a space in which a new type of sculpture comes into being. One which is not tied to a particular gallery context, nor delineated by conventional art gallery etiquette, imbuing it with the aura of the ‘art object’. Rather the joint practices of creating, filming and presenting sculptures made to be filmed offer spaces in which to rethink our relationships to sculptural objects, to think about what sculpture might be and to produce artworks which are neither tied to a gallery context, nor finished and fixed but which are mutable invitations to further practical investigation and thought.